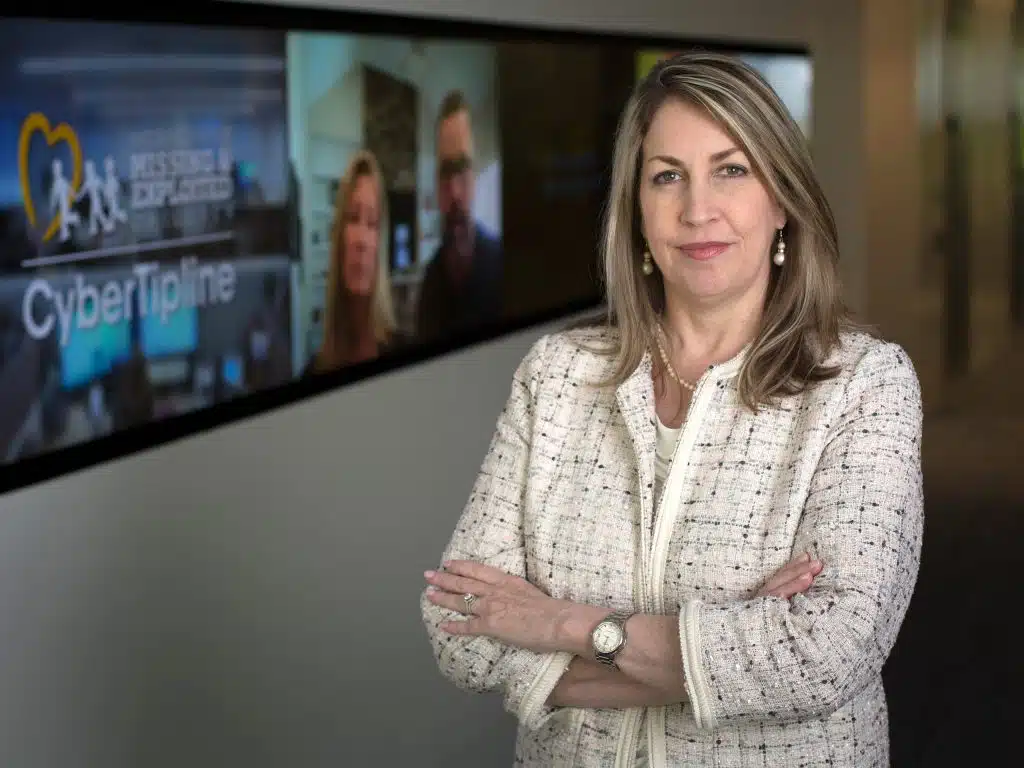

Carol Rickard-Brideau knows the power of a built environment to transform people’s lives.

She’s stepped into some of the world’s most treasured Catholic cathedrals – with their cavernous, vaulted ceilings and intricate stained-glass windows – and, like countless others before her, felt a sense of awe.

“The Catholic Church has a long tradition of using space to communicate ideas and evoke spiritual experiences,” said Rickard-Brideau.

But the Catholic architect believes that along with stirring the spirit, design can improve people’s physical and mental health.

Through her work at Little, an international architecture and design firm, Rickard-Brideau and her colleagues incorporate “salutogenic” design into everyday spaces – the grocery store, health clinic, school, fitness center and library. The term “salutogenic” means “creation of health,” and when applied to architecture refers to “measures you can take to have a positive impact on well-being,” said Rickard-Brideau, a parishioner of St. Ann Church in Arlington and graduate of Catholic University in Washington.

Growing up in a military family, Rickard-Brideau traveled around the world as a child, and her exposure to diverse spaces and designs helped inspire a 33-year career in architecture.

St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome is among her favorite structures. “You walk in and it’s almost like there are different atmospheres,” she said during an interview in her Arlington office. “You can see the stratification of smoke, and it’s just amazingly evocative.”

About 10 years ago, Rickard-Brideau began studying how the environment can have both a positive and negative impact on physical and mental health.

“I was horrified,” she recalls in a TED Talk she gave last year. TED Talks are downloadable videos on education, business, science, technology and creativity. “Architecture is supposed to be the thing we use to build civilizations and create community, and I didn’t know if the buildings I was designing were having a positive or negative effect on the people who were using them.”

Rickard-Brideau’s studies led to her current focus on salutogenic design and how it can be manifested in elements that integrate nature and natural light and promote physical activity.

She shares her ideas in articles, talks and at Little, where she is responsible for “thought leadership” around workplace issues and ideas.

Rickard-Brideau points out that although we evolved to run between 5 and 9 miles a day, we have predominantly sedentary lifestyles. About 87 percent of our time is spent indoors, and 47 percent of that time is in front of screens, according to Rickard-Brideau. “We are not using our bodies as they were designed to be used, and this has health consequences,” she said.

After long periods in a chair, blood begins to move more slowly and the metabolism and good cholesterol drop. The result is chronic diseases.

“Active design,” however, can break the link between sedentary behaviors and disease, said Rickard-Brideau. It can be as simple as posting signs on an elevator encouraging people to take the stairs or moving a garbage can out of a workspace so that employees have to get out of their chairs to throw items away.

Rickard-Brideau believes “biophilic design” is an additional way created spaces can improve health. Biophilia means “love of living things,” and biophilic design brings nature into buildings and other environments.

Because of our “evolutionary memory,” humans are wired to spend time in nature, she said. “Back to nature isn’t just a clever idiom. We actually have a mind-body connection to nature that helps lower blood pressure and reduce stress hormones.”

Even artificial replicas of nature can have a positive effect on health.

Rickard-Brideau described a study by architects and neuroscientists in which a large image of a savanna was hung at a jail intake facility in California for six weeks. Biometric measurements were taken on employees before and after the image appeared. The presence of the artwork caused stress levels and blood pressure to drop, and employees scored higher in memory and cognition tests.

Simple accents of plants, stone, water and wood in design can lower blood pressure and reduce stress hormones, she said.

About a decade ago, Rickard-Brideau helped create a biophilic space a stone’s throw from Interstate 66. Together with parents from St. Ann School in Arlington, where her two children attended, she designed a rosary garden using the luminous mysteries, complete with a pergola intertwined with grapevines for the wedding at Cana.

In this “relatively urban spot,” children can observe the natural environment as well as enrich their faith life, she said.

Rickard-Brideau also has learned that healthy building design should support human’s circadian rhythm – the physical, mental and behavioral changes that follow a roughly 24-hour cycle and respond to light and darkness.

“Our body is wired to take cues from the sun,” said Rickard-Brideau. Without exposure to natural daylight in our offices or other buildings, our body does not receive those signals and “suffers from chronic health problems,” including high blood pressure, depression and obesity.

Access to natural lighting through windows, skylights or other design elements is thus integral to healthy architecture.

Some of Little’s clients request WELL certification, which is administered by the U.S. Green Building Council and proscribes specific wellness standards. Similar to LEED certification, which is focused on environmental sustainability, “WELL is about human sustainability,” said Rickard-Brideau, adding that Little tries to incorporate many of the standards in all projects.

Rickard-Brideau said her desire to improve health through architecture and design is an extension of her Catholic faith. “It’s an effort to focus outward; it’s about helping people be productive and be healthy,” she said. “It’s about being happy in the spaces we spend our lives.”

Watch the video

View Carol Rickard-Brideau’s TED Talk, “The Brain, Environments and Wellness”

Tips for a healthier workday

Carol Rickard-Brideau suggests five simple ways to improve physical and mental health at work.

1) Move. Set your phone or another device to signal you to get up every 30 minutes and be active – go to the water cooler, bathroom or for a brisk, short walk around the office. Hold a walking meeting.

2) Drink more water. “Hydration is really important, and it’s something we don’t do,” said Rickard-Brideau, adding that we should “drink before we are thirsty.”

3) Change your posture. Get a standing desk; don’t slouch.

4) Experience nature. “Nature calms your body, calms the static in your brain, drops your stress hormones and helps you focus,” she said. Spend a few moments outside, or bring plants or images of nature into your office. Look out a window for a few moments.

5) Clear your head. Take a break to clear your mind and you’ll be more productive, Rickard-Brideau said. Sit back and close your eyes for 5 minutes to decompress before jumping back into a problem or project.